Georgia Power exploratory drilling finds promising spots

ATLANTA — Georgia Power’s deep drilling of a mile or more into Brantley County and Wayne County soil found some answers they were looking for.

Each day, carbon dioxide emitted by Georgia Power’s coal, oil and gas plants is released into the atmosphere, where it will stay for hundreds of years and heat the planet.

The unannounced exploratory drilling by the power utility giant was for contractors to see whether formations below ground level are suitable for “geologic carbon sequestration,” a method that could permanently lock away the company’s greenhouse gas emissions.

If the company tries to store carbon underground one day, its best bet may be beneath southeast Georgia’s coastal plain, according to reports.

A 78-page report on southeast Georgia found the region “holds significant promise for deep geologic C02 storage.” A separate survey concluded the northwest Georgia in Bartow County would be “challenged” to support CO2 injection and storage.

In Brantley County, a rig drilled almost a mile below the surface, collecting rock samples and imaging on the way down. Teams punched an even deeper hole 20 miles north in Wayne County.

About 4,000 feet down in both locations, they found carbon storage potential in the Tuscaloosa Formation, a sandstone layer that sits beneath portions of South Georgia and neighboring states. The formation meets the “pressure, depth and temperature requirements” for CO2 injection, the report found.

It notes higher porosity was detected at the Brantley County site, suggesting “storage conditions may improve to the South.”

Georgia Power said it conducted the drilling on private property with landowners’ permission, with the approval of the Georgia Environmental Protection Division.

Just as important is what they discovered above the sandstone — a 400-foot thick layer called the “Ridley Group,” a possible natural cap to contain the gas.

Much of the area relies on well water, and the rocks that would hold the CO2 are below the vast Floridan aquifer. Groundwater contamination is a potential hazard of carbon storage, as are earthquakes.

Right now, any CO2 wells in Georgia would need the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s approval — a process that’s likely to take years Felix Herrmann, a computational seismologist at Georgia Tech, said he’s a proponent of injecting CO2 offshore — as the Norwegians have done for years — which can mitigate many of those risks.

Carbon capture and storage is not a new technology — Norway, a pioneer in the industry, and other countries have stashed their CO2 below the North Sea for decades.

It is also used in the U.S., but most captured CO2 is used to force more oil and gas out of the ground. Collecting the gas from a power plant, transporting it by pipeline or truck, then injecting it into rocks for long-term storage is a different beast — one that has not succeeded on a large scale on U.S. soil.

SPECIAL ILLUSTRATION The technology has its detractors, and significant environmental and cost questions around it exist. But major scientific reports have found it may be necessary to limit global warming.

Herrmann agrees. “It’s not a silver bullet,” Herrmann said. “But the reason why I’m an advocate for this, frankly, is I think it’s a bit naive to think we can switch off of oil and gas tomorrow.”

Executives from Georgia Power and its parent, Southern Co., said any deployment of the technology, if it happens, is many years away. Still, it’s possible new regulations could emerge, and company executives say it’s wise to explore options now.

“In case we have to do this one day, we want to have a wealth of information to be able to be the best utility in the country to do it,” said Richard Esposito, who manages carbon storage research and development for Southern. Permeability and porosity

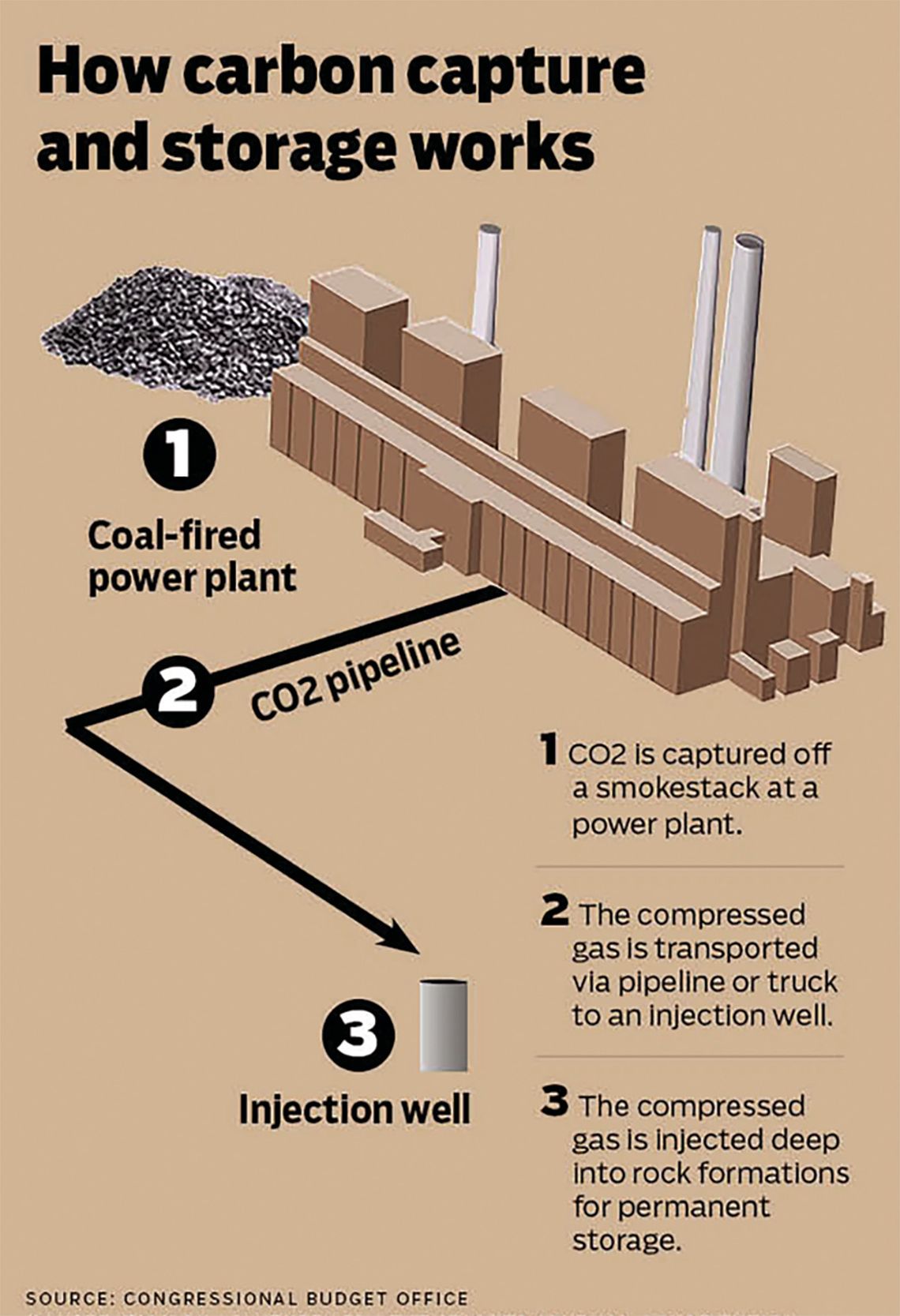

For carbon dioxide to be stored underground, it first needs to be captured from a smokestack at a power plant or another industrial facility.

Then, it must be compressed into a “supercritical” liquid-like state before it’s pumped into rock formations. Storing CO2 underground keeps it out of the atmosphere and prevents worsening global warming, experts say.

To keep carbon locked away, experts say formations must be porous enough to hold the gas and permeable enough to allow it to move through the rock.

A U.S. Geological Survey assessment from 2013 identified South Georgia’s carbon storage potential, along with large parts of the Gulf Coast.

The company licensed existing seismic data to bolster its understanding to see if parts of the Peach State might be able to store carbon, Georgia Power had to look deep underground.

Regulatory uncertainty

Whether the regulatory framework to spur a utility like Georgia Power to pursue carbon capture will exist in the future is another question.

But potentially lucrative carbon capture incentives remain. A federal tax credit for geologic carbon storage and other carbon dioxide uses is one of the few Biden-era incentives that survived in President Donald Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which slashed federal clean energy and electric vehicle credits.

Georgia Power won’t be ending reliance on fossil fuels anytime soon.

Earlier this month, state regulators approved an energy plan for the utility that will keep some coal plants — plus oil and gas ones — running for the foreseeable future. More gas is likely to be added to meet power demands of data centers.